This is the final essay which I wrote for Rhetoric I at Wittenberg Academy. It connects Richard Weaver’s essay “𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘗𝘩𝘢𝘦𝘥𝘳𝘶𝘴 and the Nature of Rhetoric” with Cicero’s texts on the artistic proofs. Enjoy!

Karl Lunneborg

Rhetoric I – M25

Fr. Cain

21 November 2025

Final Reflection Essay

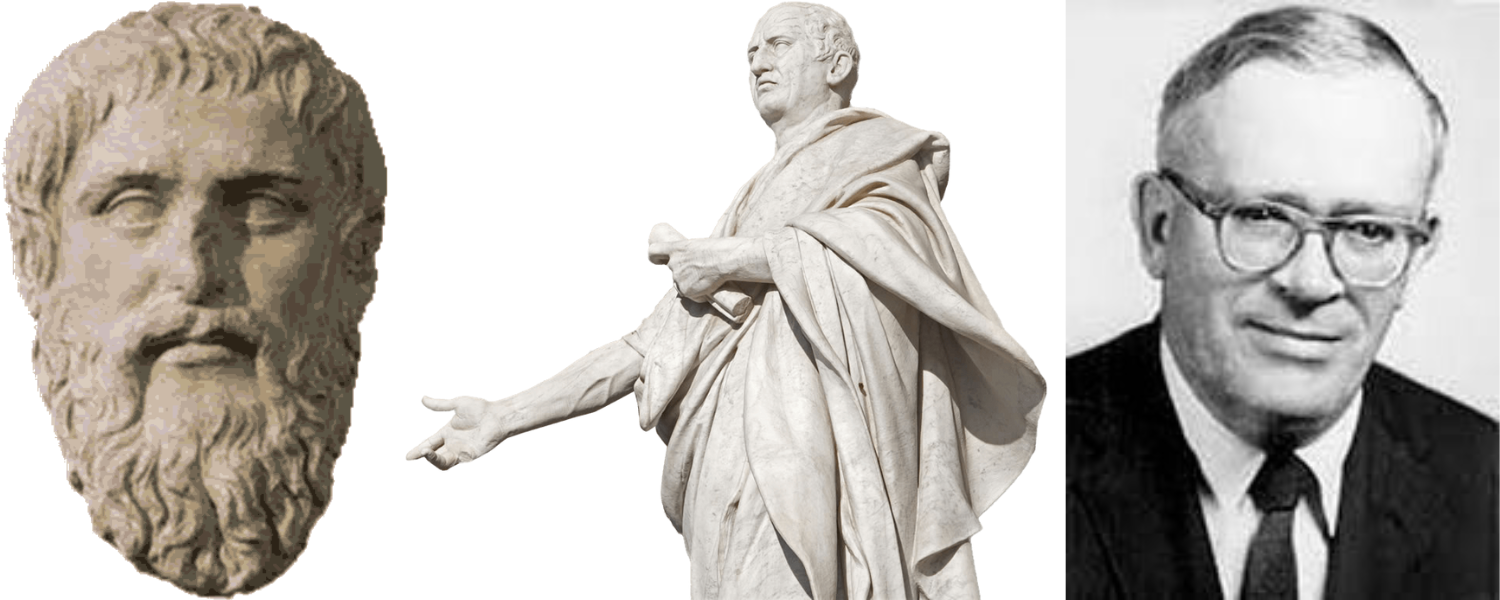

Around 370 B.C., Plato wrote The Phaedrus. Over three hundred years later, Cicero published such texts as De Oratore. Now, more than two thousand years later, there have been numerous commentaries on both of these texts. Today, I would like to focus on the essay “The Phaedrus and the Nature of Rhetoric” by Richard Weaver, and the book How to Win an Argument, a collection of Cicero’s works about Rhetoric, compiled by James May. Specifically, comparing Weaver’s essay with May’s chapter entitled Discovering the Sources of Proof, which covers the Aristotelian modes of proof, including Logos, Ethos, and Pathos.

Early on, Weaver makes note of a warning against literal reading, made by Phaedrus and Socrates. There was a myth at that time, that Oreithyia was carried off by Boreas, god of the North Wind, on the banks of Illisus. However, there was also already a scientific explanation disproving this, namely that she had been on the banks, there, and the north wind blew her away. Obviously, there is a stark similarity between the two tales. But this exemplifies the poetic, imaginative nature of a speaker when he is composing his speech. Cicero, in De Oratore, says that when one is dealing with an argument, he must think both how to treat it, and how to discover it. The proofs which the speaker must figure out how to treat are referred to as nonartistic proofs. A nonartistic proof is one of written documents, contracts, etc. But perhaps the most important part of writing a speech is considering how to discover the different parts of the nonartistic proofs. The rhetorician does not disregard the facts; he builds on top of them. Just as the myth was created that Boreas took Oreithyia off, a speaker must draw up the facts of the matter, and overlay different portions of his art on top of these facts to convince his listeners.

Further, Socrates comments that the tales of scientific explanations are irrelevant. Why? As Weaver states, they give, at best, a “boorish sort of wisdom.” A speaker who relies merely on the nonartistic proofs is going to give boorish speeches, and none of his audience will be convinced, let alone interested enough to pay attention the whole time. An archaeologist could try and find the foundations of the Garden of Eden, but he will not succeed until he looks further than just physical remains, to a higher level. Perhaps, then, looking for what the Garden of Eden was, and what it meant that humankind was removed from it eternally. “Real investigation goes forward with the help of analogy” (Weaver).

The artistic proofs, visibly Logos, Ethos, and Pathos, now deserve an explanation. Logos is an appeal to reason. As Cicero put it in De Inventione, “since assent has been granted to statements that are undisputed, even the point that would seem in doubt when asked by itself is, by analogy, conceded as certain, because of the method employed in putting the question.” As we have found previously, the facts by themselves prove to be quite boorish. However, with the facts analyzed alongside an example, the speaker can draw the audience in, and towards the conclusion he is laying out. Ethos is an appeal to credibility, virtue, or common sense. Cicero says that such things as the character, customs, deeds, and life of both the speaker and one for whom he is speaking play a very large role in convincing people. James May, who gives commentary throughout How to Win an Argument notes that Ethos is likened to blood running through all the body. It is not found in one place only, but all over, giving the audience constant reason to listen to this man and what he has to say. Lastly, Pathos is an appeal to the emotions of the listeners. May again comments that Cicero often said this was the most effective means of persuasion. He continues, saying that while Ethos called up milder emotions, Pathos summoned the strongest emotions, grief, passion, among others. Even though it may be the most effective means of persuasion, it cannot be used by itself. Because feelings on their own mean nothing. Likewise, without Logos or Pathos strengthening it, Ethos is a useless argument. As is the case with Logos. Yet e7ach of these three come together to build a most powerful argument.

As The Phaedrus continues, we see the reading of the dialogue of Lysias on the lover and the non-lover. Socrates sits, and listens to Phaedrus read this dialogue. This speech, for speech it is, is framed so well, with such mastery of the artistic proofs, that Socrates, although he has critiques, cannot help but say that the speech was “quite admirable” and “the effect on me was ravishing” (Plato). However, Socrates removes himself from the feelings made by the delivery, and turns himself towards the actual content. The Pathos in this speech is so strong, that if a man does not think of the actual words which are being spoken, he will become so enthralled that he will wholeheartedly agree to what the speaker is saying without giving it a second thought. The indirect Ethos arguments are also strong, for Lysias makes it clear that he has studied this intently. Socrates himself remarks that “he is a master in his art and I am an untaught man” (Plato).

Weaver here mentions that this whole scene brings to the surface Plato’s thesis for the entire book, and as a good student of Socrates, it is phrased as a question. Weaver marks it as thus: “[Plato] is asking whether we ought to prefer a neuter form of speech to the kind which is ever getting us aroused over things and provoking an expense of the spirit.” The neuter form which he refers to would be one built merely on the unartistic modes of proof, the documents, contracts, etc. Although one might see a correlation, those documents are not in themselves a form of a Logos argument. A Logos argument, as we have seen, uses an example to draw the listener in. Without that artistic addition to the raw facts, a speech would be so boring that no one would care to listen. However, with too many emotions piled on top of the speech, it draws the listener away from the content, to a potentially dangerous extent.

Here Weaver goes into a description of the neuter language. It is framed with its uses and upsides, such as objectivity, and is likened to the interactions of non-lovers. There is no bias or particular persuasiveness in it, so there can be no trap such as Socrates noticed in Lysias’ speech. It merely lays down the facts for the audience to come to their own conclusion with. It also does not “excite public opinion,” as Weaver says. A lover exchanging words with another lover would do just that. But the non-lovers will merely be regarded as exchanging words of friendship, or passing time. Weaver explains how the audience is most likely to side with the man who has the greater degree of inclination. For the more partiality shown, the more interested people will be to listen. However, as Socrates says, “to tease [the lover] I lay a finger upon his love!” One who seeks to critique a man who has shown the side which he takes has a hard time, because he does not want to offend the speaker. But if the man’s opinion is unpopular, there will be so many displeased that this will not be a problem for the one critiquing. Yet we find that in humanity, such neuter language does not exist as it is framed. Weaver summarizes neuter language well, saying that “neuter discourse is a false idol.”

Weaver says towards the end of his essay that the movement with which Rhetoric moves the soul cannot be explained logically. This is because Rhetoric is aimed at greater truth. When used properly, the entire point of Rhetoric is to move the soul towards the ultimate good. However, as we have seen, Rhetoric can be twisted, and draw the listeners astray. Cicero’s summarization of the three artistic modes of proof makes this clear. In De Oratore, he says that the method used in Rhetoric is comprised of “proving that our contentions are true, winning over our audience, and inducing their minds to feel any emotion the case may demand.” Rhetoric is very strong, able to move the hearts, even the souls, of the listeners, and at the core of the community, as Weaver says, there is a struggle between powers for the means of rhetorical propagation. Although Rhetoric is an art which is losing popularity today, there is no shortage of people trying to influence one another. Nevertheless, the pinnacle of Rhetoric is to guide men’s hearts towards the true, the good, and the beautiful; the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

Weaver concludes his essay on The Phaedrus by saying that the rhetorician will be brought face to face with the supreme truth once he goes beyond thinking only of methods of Rhetoric. Cicero goes over each of these methods, visibly, Logos, Ethos, and Pathos. Logos, the appeal to reason, utilizes examples to guide men toward the truth. Ethos flows throughout the speech as blood runs through the body, and is an appeal to the speaker’s credibility. Finally, regarded as the most effective means of persuasion, Pathos is the appeal to the listener’s emotions. On their own, none of the proofs make a complete argument, but when the speaker brings them all together, his argument is unlikely to be contested. However, listeners ought to be careful, for not all rhetoricians use these proofs well. If a speech is structured with too much emphasis on Pathos, the listener will become enthralled, accepting whatever is being said without thinking it over. One might think that it would then be better to resort to a neuter form of speaking, but as Weaver said, “neuter discourse is a false idol.” Relying only on nonartistic proofs results in a boorish speech which no one cares to listen to. So, just like the myth of Oreithyia and Boreas, the rhetorician takes the plain facts which he is given, and uses the artistic proofs to draw the listener in, and towards the point he is making. This point, when Rhetoric is used correctly, is the ultimate good. Because rhetoric has the power to move the soul, the best use of it is to move the soul towards the Truth, that is, Jesus Christ.

Bibliography

Weaver, Richard. “Phaedrus and the Nature of Rhetoric.” Rhetoricring.com, www.rhetoricring.com/tribute-to-richard-m-weaver/treasury-of-richard-m-weaver/weavers-top-ten/phaedrus-and-the-nature-of-rhetoric/. Accessed 22 Nov. 2025.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius, and May, James M. How to Win an Argument: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion. Princeton; Oxford, Princeton University Press, 2016.

Plato. Great Books of the Western World; Vol 7: Plato. 1952. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, Twentieth Printing, University of Chicago, 1975.

Author Profile

Latest Posts

TravelJanuary 10, 2026The Travel Times – VI; Texas Part Three: Amarillo, Cadillac Ranch, and the Big Texan

TravelJanuary 10, 2026The Travel Times – VI; Texas Part Three: Amarillo, Cadillac Ranch, and the Big Texan PoetryDecember 28, 2025On Death

PoetryDecember 28, 2025On Death PoetryDecember 27, 2025Homines Modernæ Ætatis

PoetryDecember 27, 2025Homines Modernæ Ætatis EssaysDecember 8, 2025Rhetoric I Final Reflection Essay

EssaysDecember 8, 2025Rhetoric I Final Reflection Essay

No responses yet